Nato’s Parliamentary Assembly recently published what some have called a “scathing” report on Turkey.

Until now, Nato had given almost no input on the country’s deterioration in human rights and rule of law, despite Turkey being one of its largest member states.

Cafer’s story

Cafer attended the Turkish naval academy from 1992 to 2000, when, upon graduating, he joined the service.

After dedicating a further 15 years to the navy, he was seconded to the Nato post in Belgium.

He relocated with his family – a wife and three young children. For that next year – 2015 to 2016 – they lived in Brussels.

On the night of 15 July 2016, he was shocked to hear of the attempted putsch in his home country.

In the following months, Cafer saw several of his Nato colleagues return to Turkey only to be arrested, but he never thought something like that would happen to himself – an innocent man.

On 10 October, he received a message from his superiors in Turkey, instructing him to return for an “urgent” meeting on standardisation issues.

As standardisation is not a pressing matter, it appeared a bit odd.

Cafer’s friends cautioned him, saying: “It’s clearly a trap”. But Cafer believed that an innocent man had nothing to fear.

In the worst case scenario, he would be able to prove his innocence in court, he thought.

Besides, this was his military superior’s order and he had to obey.

His wife felt the same. And so, on 12 October, Cafer said farewell to his family and departed for Ankara.

Cafer’s first night back in the Turkish capital was uneventful.

On the fateful day of 13 October 2016, he visited old military friends, again without incident.

Later that day, he attended the meeting at the Turkish military’s general staff HQ.

As was customary, he had brought a box of chocolates for his navy commander.

But handing them over, he saw a glimpse of shame in the commander’s eyes – that is when, he says, he knew it was indeed a trap.

The meeting dragged on, all the while with Cafer realising they were talking just to keep him there.

Feto accusation

They were holding him at the general staff HQ while the naval forces command HQ tipped off the counter-terrorism police that they had a “Feto” member in their midst.

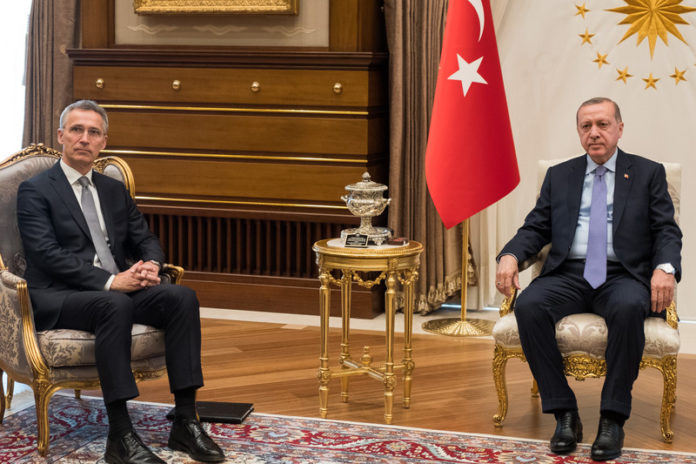

“Feto” refers to a follower of Fethullah Gulen, an Islamic cleric and politician who lives in the US and whom Turkish leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan has blamed for the coup attempt.

There was no evidence of this allegation against Cafer.

But a navy admiral called Cihat Yayci had ordered his arrest due to what Cafer now sees as anti-Nato and anti-Western sentiment in the current Turkish establishment.

The officers who arrested Cafer told him that they did it on Yayci’s instructions.

The admiral, who made his name in the post-coup crackdown and who has since been promoted to chief of staff of the Turkish naval forces, was also named in documents in Cafer’s subsequent trial.

Like many others, including EU countries’ intelligence services, Cafer believes that a list of those viewed as a threat to the regime was prepared long before the coup attempt.

“I am an outspoken person. I always say what I believe, which is not always parallel with the official Turkish ideology,” he told this website.

Despite the lack of evidence, the counter-terrorism squad accosted Cafer as he went to leave the HQ.

They searched him for items considered in Turkey to be proof of Feto affiliation – such as possession of a $1 bill. Finding nothing, he was still arrested.

“It’s very tragic and I can’t explain it. Being in the [naval] service together, it’s beyond brotherhood. Some of these men, we’ve worked together since 1992”, he said.

“We’re closer than family … It’s like you see in the movies, where men endanger their lives to save their comrades. But the admiral [Yayci], he has never been true to military values and morals. He’s long been known for this kind of [political] style, so I’m not that surprised that it was him who wanted my arrest,” Cafer told EUobserver.

Gymnasium camp

Following his capture, he was taken to a gymnasium turned into a makeshift detention facility.

It was located near Erdogan’s presidential palace in Ankara. The prisoners could see it from the windows and people in the palace could likely see them.

There were over 100 inmates cramped inside, mostly government officials and military personnel.

Cafer had previously seen pictures of this facility, and of half-naked prisoners lying on the floor, but he recalled that “the atmosphere of actually being there was very different”.

Their meals consisted of two pieces of bread for breakfast and another two pieces, with two spoonfuls of rice and two spoons of vegetables, for dinner.

The heating was turned up during the warm days, while the air conditioning was turned on during the cold nights.

There were no spare clothes and the inmates rarely showered. When they did, they were given a napkin as a towel, being forced to then sign off that they had been provided with adequate washing facilities.

No one had shoes. Five pairs of dirty slippers were provided to use in one of the three toilets that they shared.

At night, while bright spotlights glared, inmates tried to sleep on the thin, blood-stained mattresses scattered on the ground.

There was blood all over the gymnasium.

Bloody bandages lay in corners and under chairs, which inmates were banned from sitting on.

The police were violent and quick to anger. They were constantly shouting threats, swearing, and beating inmates.

Every day, a medical team would come to check on the detainees, but the guards always stood within earshot.

No one dared to speak up. Instead, the inmates found solace in confiding in each other.

Cafer relayed some of the stories he heard.

Other victims

One of these concerned two Turkish medical professors from the Bahrain Royal Hospital in Manama, who had been forcefully deported and then detained at the gymnasium.

They were invaluable to the other inmates, giving them advice on how to stay healthy during their ordeal.

One day, one of the professors returned from an interrogation session crying.

He had been tortured: shaken, beaten, and then forced to lie on the ground while a guard put a gun in his mouth.

The guards had also pretended to throw him out of a window.

They then told him to run down the corridor. He ran for his life, thinking that they would shoot him in the back and pretend that he had tried to escape.

In another case, an army colonel had already spent three months in prison before being returned to the gymnasium for interrogation.

He was repeatedly taken away and tortured.

When an attorney visited him, he threatened that they would also imprison his wife if he did not confess.

The couple had two young daughters. The attorney stressed that the girls would be left without their parents.

The colonel was, naturally, distressed, but he did not want to give false information, which would, he feared, be used as ‘evidence’ to unjustly imprison other innocent people.

Cafer also met an insurance broker during his time at the camp.

The broker’s business had been thriving, drawing the attention of a neighbour who frequently asked to buy him out.

After the coup attempt, the broker was arrested when the neighbour tipped off the authorities on his alleged “Feto affiliation”. The neighbour then took over his business.

Such manipulation of the current climate in Turkey is common, fomenting distrust between neighbours, friends, colleagues, and even family members.

Cafer spent 12 days in these conditions.

Prior to the coup attempt, the maximum period of detention without a court hearing was four days, but under the state of emergency this went up to 30 days.

Some of Cafer’s fellow inmates endured the full month. “I was very lucky to be taken to the courthouse on the 13th day”, he said.

Show trial

Inside the court, Cafer was bombarded by statements instead of questions.

“You are working with Nato” and “you have very good English”, the prosecutor said, in what was meant to be proof of his Feto guilt.

He was told he had insulted Erdogan on Twitter – a serious crime in Turkey and an accusation specifically endorsed by Yayci, the naval commander, according to court documents.

But Cafer disputed this and asked to see the Twitter account.

When it was shown, it emerged that some of the ‘incriminating’ tweets had been posted while Cafer was an inmate at the gymnasium.

Others had been posted during the court hearing itself.

“How can that be me?”, Cafer pleaded, but the prosecutor did not change his line.

He was also accused of having used ByLock, an encrypted smartphone application – a go-to charge in the post-coup purge, which requires no substantial evidence of actual coup involvement to establish guilt.

It was decided that Cafer should be held in jail pending the final outcome of the trial.

Sincan prison

He was taken to the Sincan High Security Prison outside Ankara, still in the same summer clothes he had been wearing 13 days earlier for his meeting at the military HQ.

He realised that he was weak and emaciated, having lost about 7kg in weight in that short space of time.

He was put into a three-person cell, which already held four others. There were three beds and a thin mattress on the floor.

When the United Nations special rapporteur on torture visited Sincan, they were given an extra mattress, prompting jokes that it was “like a Hilton [hotel] suite now”.

Cafer heard of other cells being given fresh coats of paint for the occasion, but he and his fellow inmates never met the rapporteur.

The five cell mates shared food allocations meant for three.

It fell below 15 degrees Celsius at night, but they were given no heating.

They did have a kettle to make tea, using the boiling water to bathe with and keep warm.

The five men were allowed very little contact with the outside world.

He had been gone for two months before Cafer was allowed to send a letter to his wife.

He could not phone her and found it very hard to handle the isolation, but he said that three alleged members of Isis, an Islamist extremist group, in an adjoining cell, with whom he and his cellmates spoke through the wall, were allowed to call their families.

Tortured to insanity

He also brought to light the horror stories of other inmates at the Sincan facility.

One army major who was being held there, Cafer said, had previously been taken to the Turkish special forces HQ, handcuffed, and tortured for three days with electric shocks.

“It felt like my body was on fire”, the major told Cafer.

Unable to endure the pain, he made a false confession.

He told the judge during his trial that it had been extracted under torture, but he was still sentenced to life in prison.

The major was later released on parole, after 27 months of detention, but his sentence remains in force pending further hearings.

Erdogan’s special forces HQ was used as a torture facility for at least one other Sincan inmate, Cafer reported.

The second victim was waterboarded there, he told Cafer.

He was forced to lie on the ground with his hands tied with plastic cords. He broke the wires three times while trying to cover his mouth, giving him severe scars.

He also received a life sentence.

“The judges are like puppets – they don’t think, don’t make the decision, they just do what’s requested of them”, Cafer said.

Cafer went to the prison hospital several times.

He twice saw an inmate who looked as though he had lost his mind – he would sporadically laugh, cry, and talk to invisible people.

It later transpired that the fellow prisoner was a lawyer from Konya in central Turkey who had stood up to Erdogan’s ruling clan in a 2013 corruption affair.

The lawyer was arrested after the coup and tortured into insanity, but still has 10 years left to serve in prison despite his mental incapacity.

Cafer’s escape

Cafer spent 11 months inside Sincan’s walls before being given access to his file.

The 160-page document went on at length about Fethullah Gulen’s biography before accusing Cafer of being a member of his purported conspiracy.

In October last year, the prosecution failed to present evidence at his defence hearing in court.

They dropped the initial Twitter insult charge, but they kept the ByLock accusation, and put forward new Twitter charges.

In February this year, they failed again to present evidence, and Cafer was freed on bail – 16 months after he first returned to Ankara.

His diplomatic passport had been revoked and he was to report to police every Saturday.

But Cafer still had his normal passport and upon hearing that Yayci, the admiral, wanted him re-arrested, he fled the country.

By March 2018, he was reunited with his family in Brussels.

The escape route was “dangerous”, he said. It involved a Turkish airport and passage through Greece, he added, but he gave no further details in order not to cause problems for other regime victims who were still trying to get out.

“The authorities in Greece were very kind, including the police. They comforted me and the other refugees. It was a great relief”, Cafer said.

Belgian authorities also helped by granting him refugee status and paying him welfare to replace his lost Nato income, he said.

Life in Brussels was different now compared to when he used to be a Nato official in the city, he noted.

He was “very grateful to Greece and Belgium” for their aid, he added.

Nato commiserations

But he said Nato itself let him down.

Cafer’s wife sent several letters to senior Nato officials asking for help during his 16-month detention, but few of them replied, and those who did offered only their commiserations.

Cafer’s friends in the EU and Nato capital visited him and collected money for his family.

They knew he was innocent, but no member of any international institution or agency ever spoke out in his defence.

“It was a big disappointment for me. All my life, I stood for morals and democracy. When I most needed help, I did not receive it. It’s discouraging,” Cafer said.

The Nato Parliamentary Assembly’s ‘scathing’ report on human rights in Turkey was also disappointing, he said.

The assembly’s papers are non-binding. This one also said nothing to hold Turkey to account for its crimes against political prisoners, such as Cafer and the others whom he met in Erdogan’s dungeons, he told EUobserver.

“I’m afraid that Nato will do no more than raising the regular eyebrows behind closed doors”, he said on the follow-up to the report.

He has a right to be concerned because his family and friends back in Turkey continue to face harassment.

His brother was dismissed from his job in the Turkish military.

He got it back in return for denouncing Cafer as a “traitor” and for changing his family name.

Police pay regular visits to his parents and siblings. Some friends and neighbours have also urged them to disavow Cafer, in a sign of the raw nerves in Turkish society.

They may be in Brussels, but Cafer, his wife, and their three children do not feel safe.

Erdogan has boasted about snatching “traitors” from overseas, and there have been instances of abductions and forced deportations.

Moral duty

Cafer spoke to EUobserver despite the risk of further reprisals because, he said, it was his moral duty.

“I was lucky to leave the prison, to leave Turkey. There are so many still in prison on baseless accusations,” he said.

“We who are still free should speak for them. It’s the least we can do. It’s the moral thing to do,” he said.